Question

What are good practices for design research in healthcare?

The short answer

During the workshop, participants identified ‘relationship diplomacy’ and ‘care & reflexivity’ as good practices for design research in healthcare settings. After further analysis of the participants’ contributions we identified four additional strategies: ‘playfulness’, ‘informality’, ‘clarifying the purpose of design’ and ‘self-protection’.

The elaborate answer

Three events described informal meetings between the designer and part of the clinical staff.

“An informal meeting in the pub lead to a significant case study in the NHS”

– Participant 3

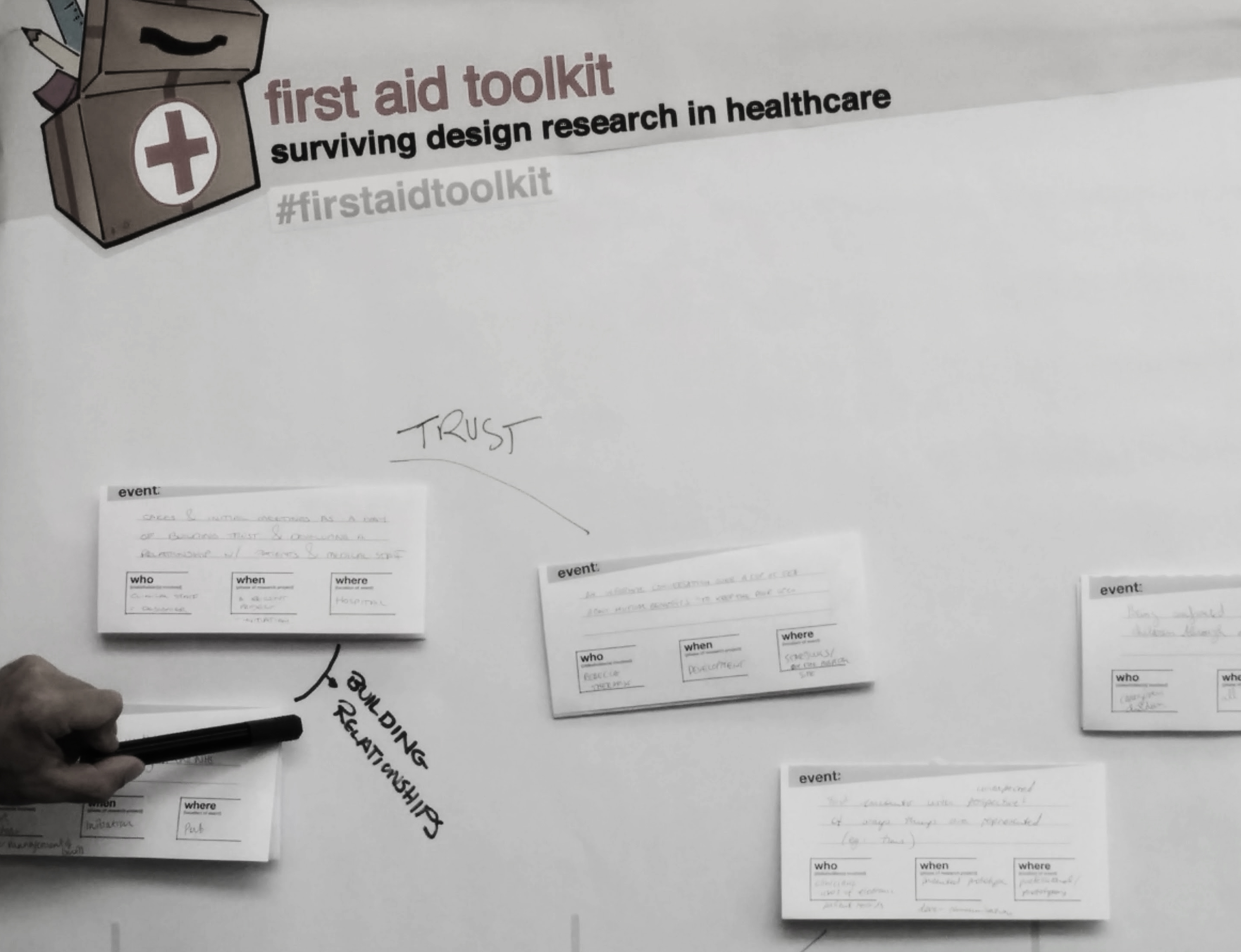

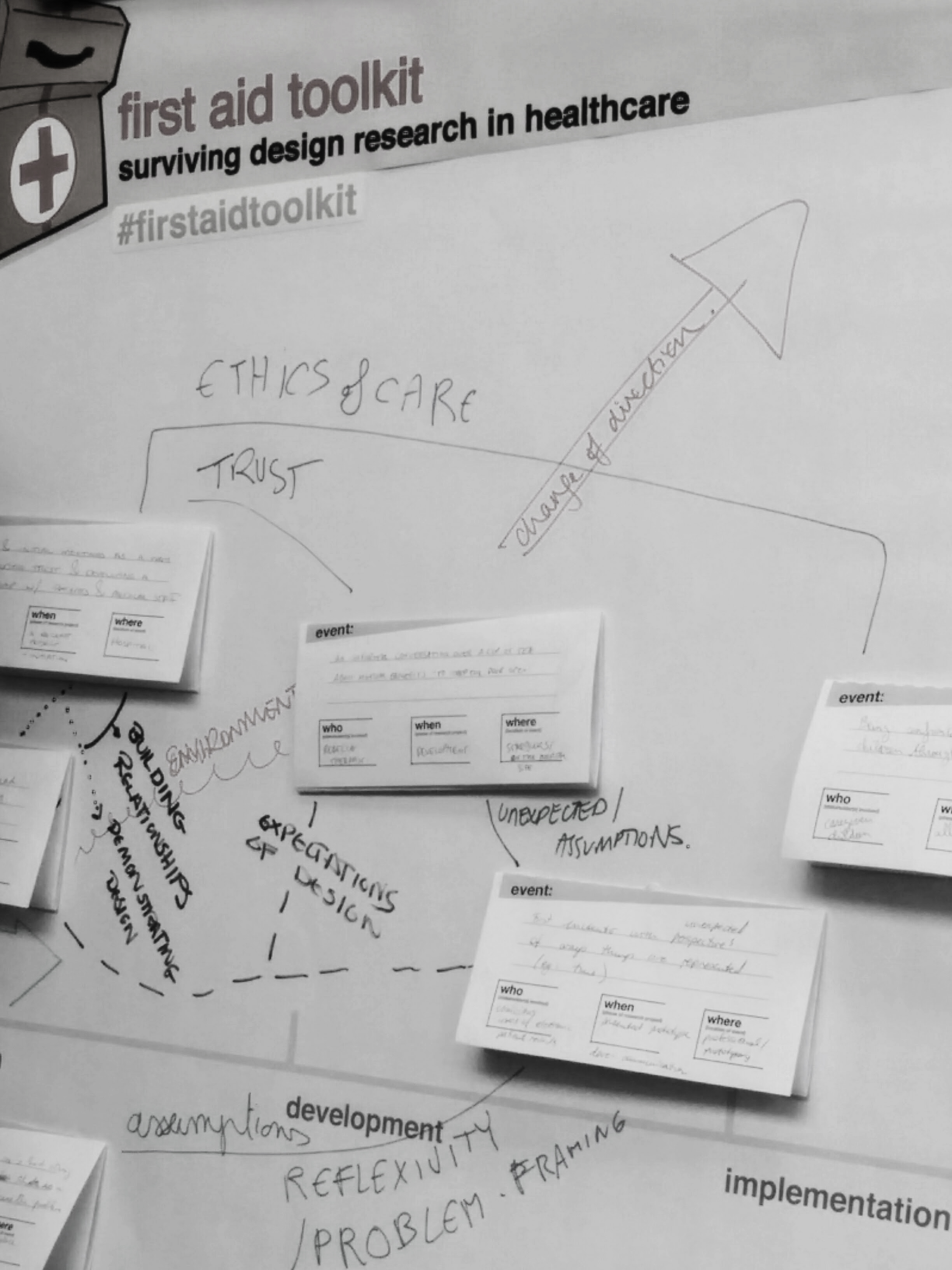

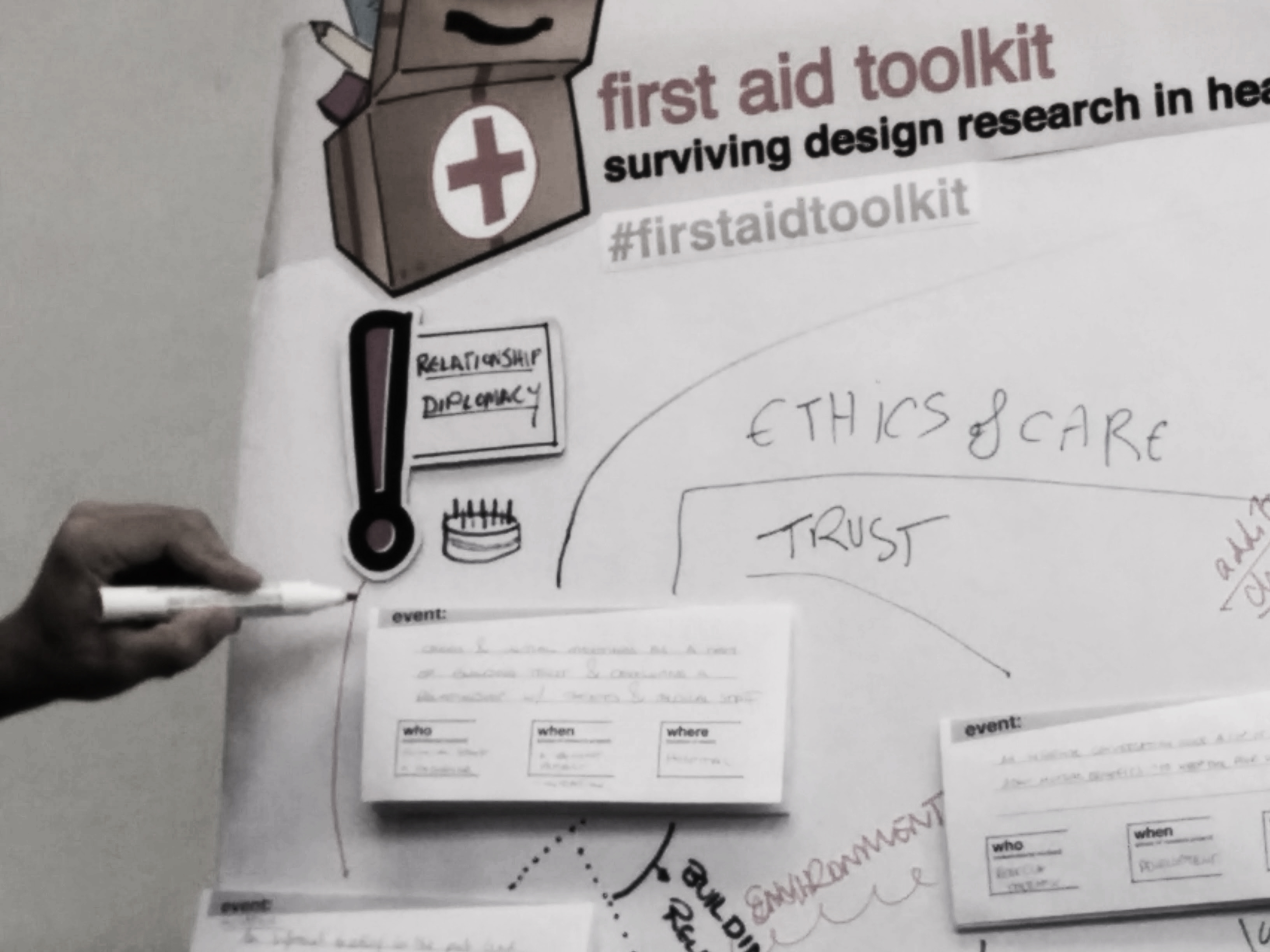

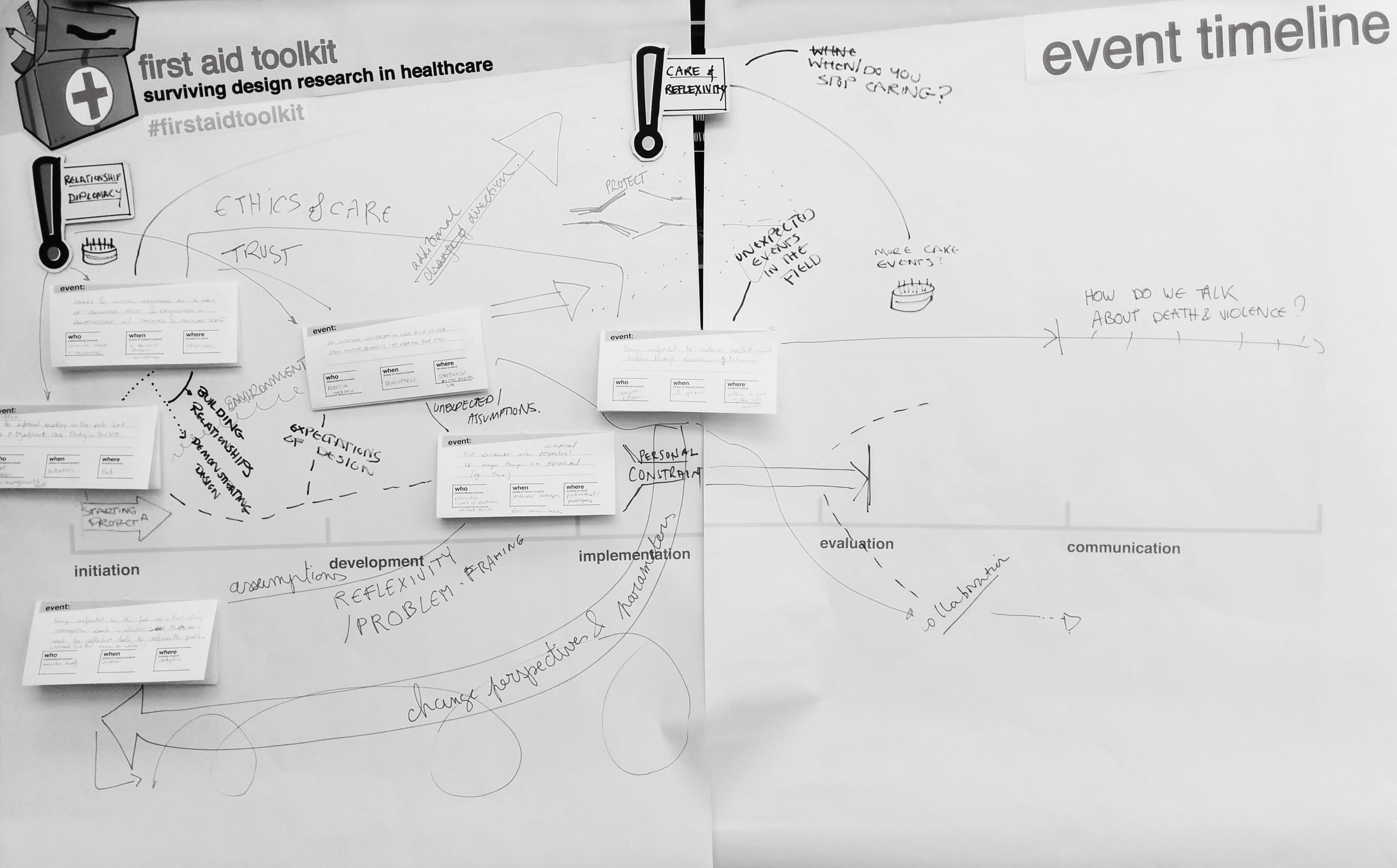

Participants grouped these events together under the theme ‘relationship diplomacy’. This theme describes the importance of managing relationships while working on a design project in healthcare setting. According to the participants, this strategy is most applicable to the beginning of the design project, especially during the initiation and development phases. Reflection on this strategy raised the question of how to build relationships and create diplomacy between the clinical team and the designer.

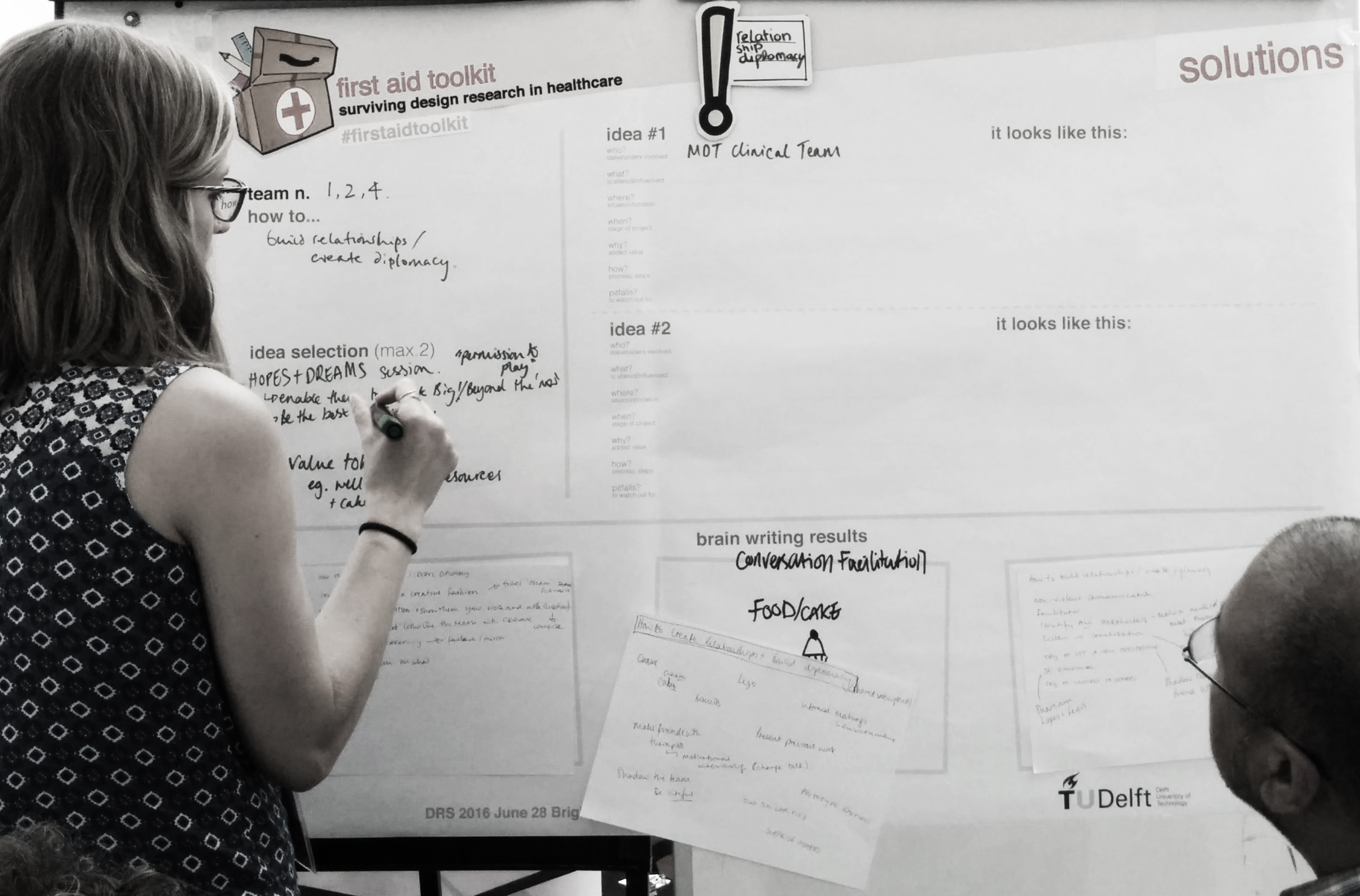

The team that elaborated on the strategy ‘relationship diplomacy’ had ideas to invite people to reflect on a dream scenario in a creative fashion. They also discussed the possibility to prepare a presentation to show their work and trigger questions from those outside the field of design. Finally, they looked for ways to make the concept of ‘team’ tangible or find a tangible way to facilitate conversation among team members.

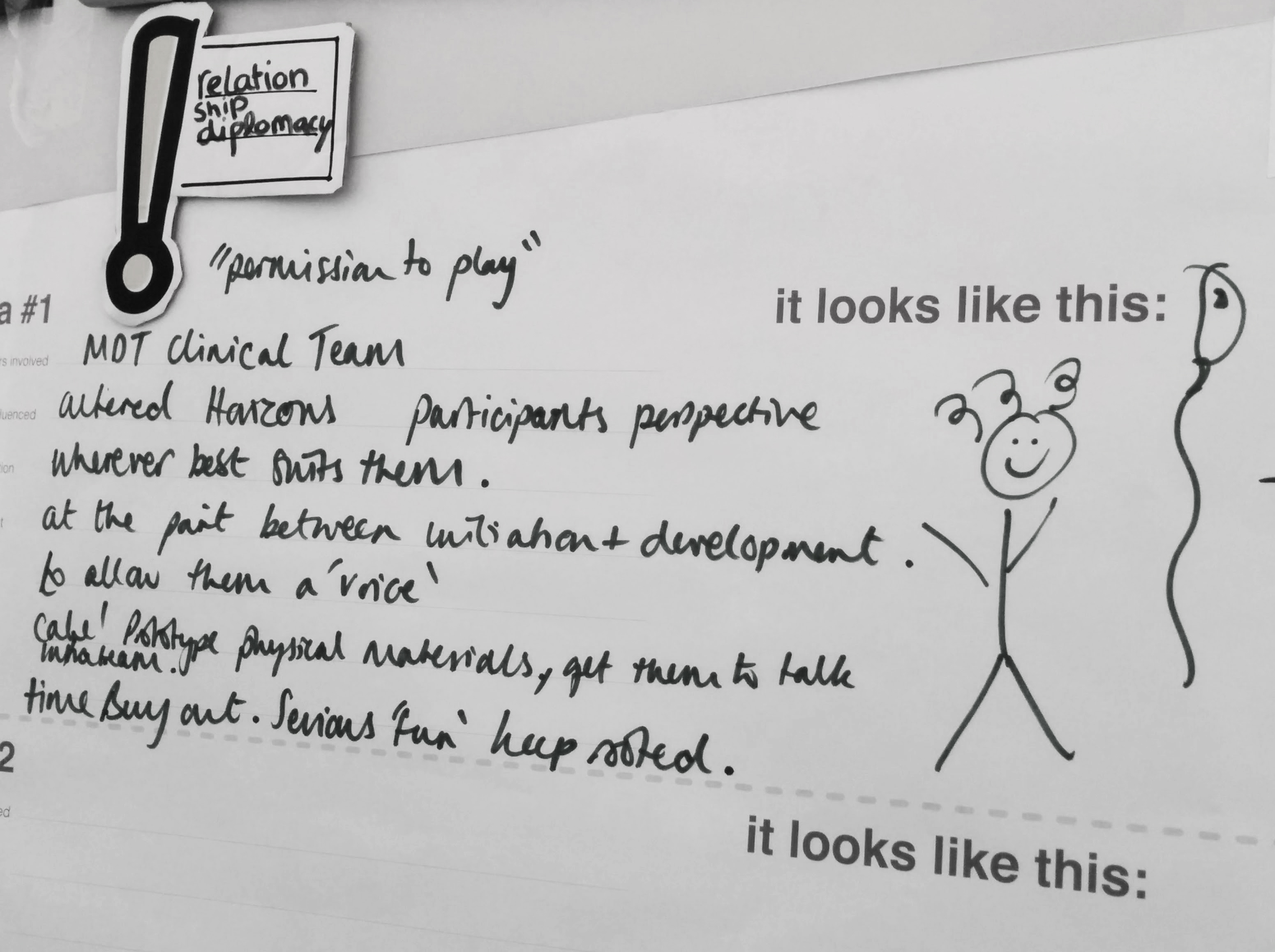

Surprisingly, the final solution proposed by the team of participants describes a session which should not directly involve the clinical team. Instead, the proposed design solution introduces the concept ‘permission to play’ which describes a free play session that enables designers to think big and ‘beyond the now’ (fig. 1). The participants suggest that play with physical materials may facilitate designers to communicate their work with the clinical team at a later point. Apparently, the notion of ‘playfulness’ appears to be an important strategy for designers working in healthcare.

‘Informality’ itself may also represent a viable strategy which allows the designer to find common ground without judgement. In the interviews, participants discussed the issue of design versus authorities and the need to build trust, which was deemed necessary for participatory design and ‘co-design space’. Informality may be a way to accomplish trust and diplomacy because it allows professionals, both healthcare providers and designers, to relate to each other at a personal level. We would therefore recommend designers to employ informality to clarify and give examples of what design means and can do before starting a project to involve all stakeholders. Or as concretely expressed by one of the participants:

“Have more cake events”

– Participant 1

where stakeholders and the designer share a cake while discussing potential research.

Creating common ground also requires the designer to both ‘clarify and convey the purpose of design’. While interviewing each other, some participants briefly wondered ‘what design should be’ and ‘what the role of design is’. In another group, participants indicated potential answers to this question by describing design as tangible demonstrator, or design as concerning outcomes. From these discussion we inferred that clarifying the purpose of design would be good practice when working in healthcare. We suggest that in order to clarify its purpose both for themselves as well as for others working with them, designers should explicitly formulate the aim of the research actions undertaken.

The three other events concerned topics such as confrontations with violence to patients, strong personal assumptions and unexpected perspectives. According to the participants, these confrontations can be mitigated by being reflexive, i.e. adaptive. This strategy was described as ‘care & reflexivity’.

“Being confronted to the fact one’s had strong assumption about a situation, there is a need for reflective tools to reframe the problem addressed and the means to address it.”

– Participant 5

This strategy raised several ‘how-to’ questions, including how to (dis)engage in a care relationship and how to use anthropology and sociology work for reflexivity. This strategy seems mainly needed in the implementation phase of the research.

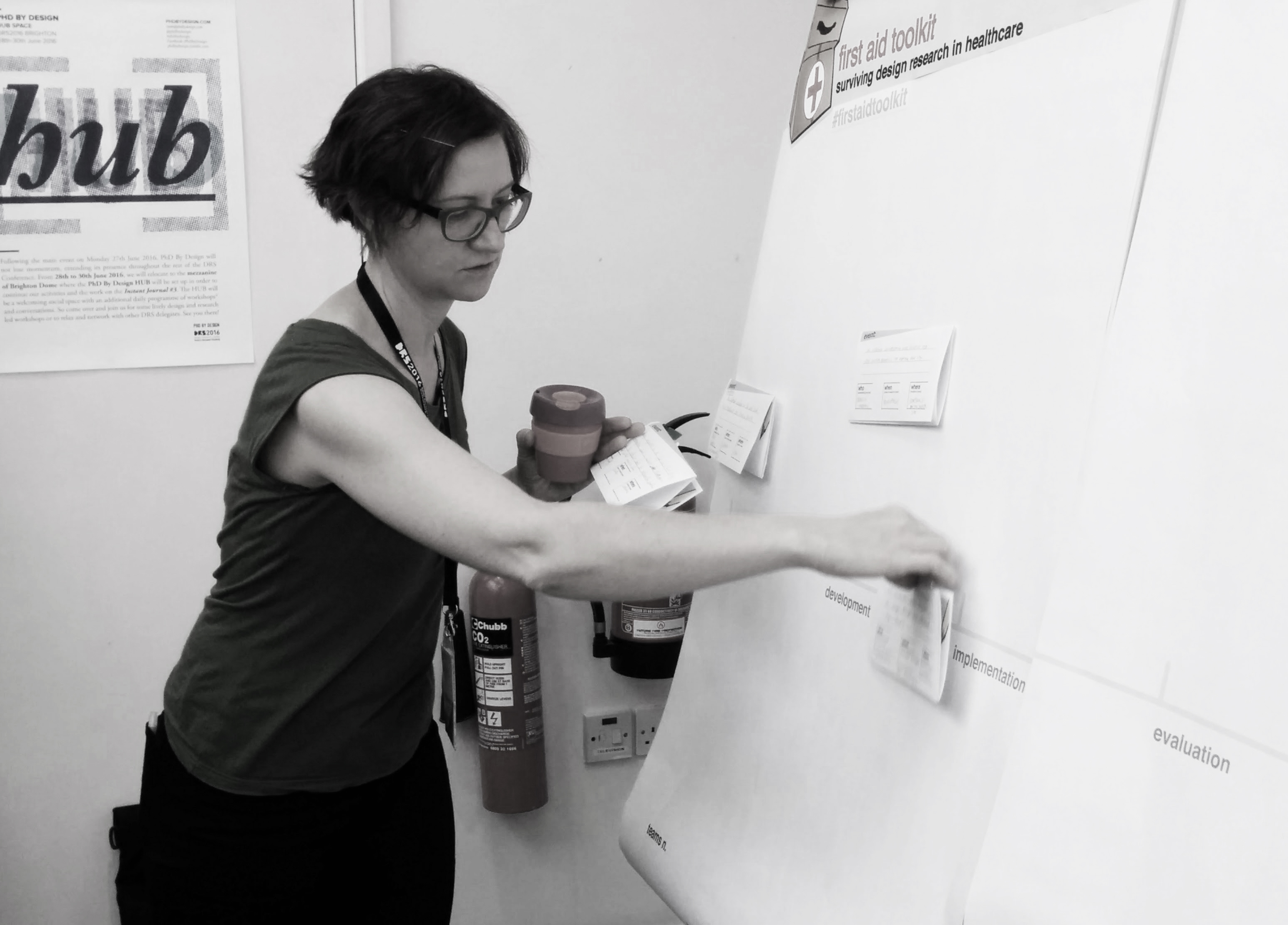

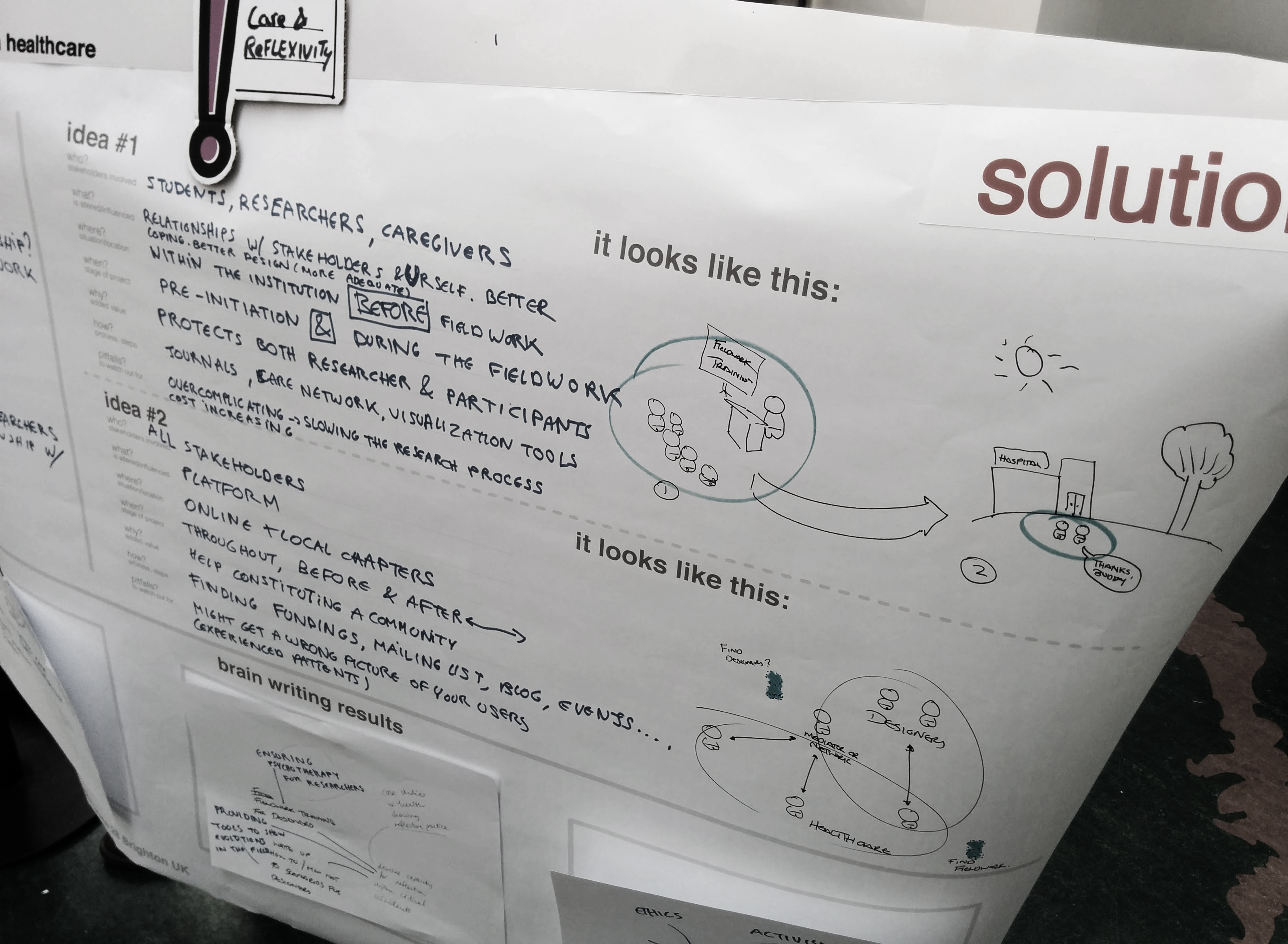

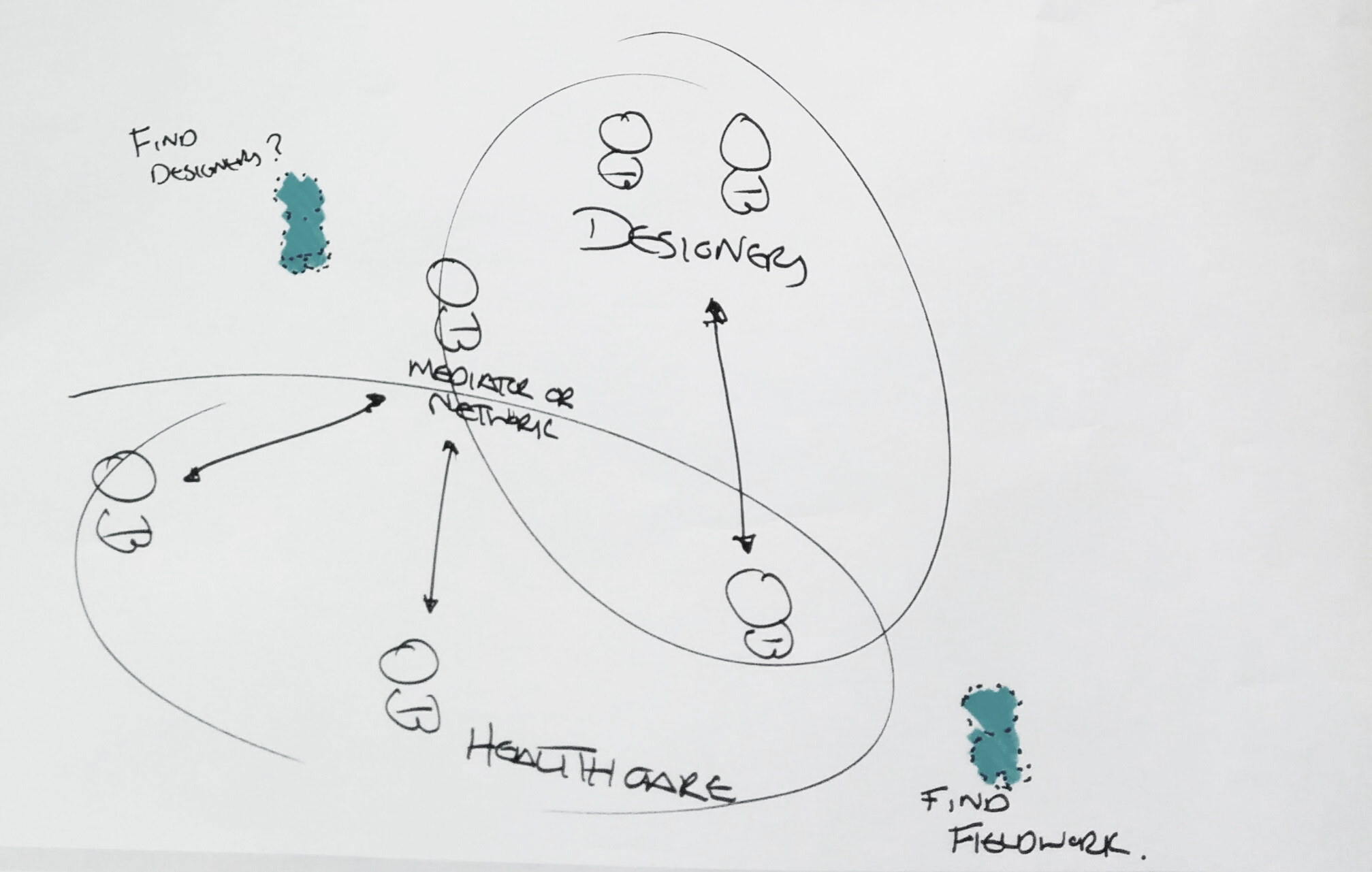

The participants suggested the use of a online and analog platform (fig. 2) for all stakeholders throughout the project in order to constitute a community.

This concept stemmed from ideas on conviviality tools and tools to show evolution in the field. The participants feel that this would develop capacity for reflection upon critical incidents.

We argue that ‘self-protection’ is also a key skill and strategy designers need to adopt. Because part of the design work is establishing an emphatic understanding, designers may develop an attachment to their users. This attachment can be troublesome when unjust actions carried out against vulnerable patients are experienced or when patients pass away during the design project. Two of our participants mentioned this as well:

How do we talk about death and violence?”

– Participant 6

“When do you stop caring?”

– Participant 1

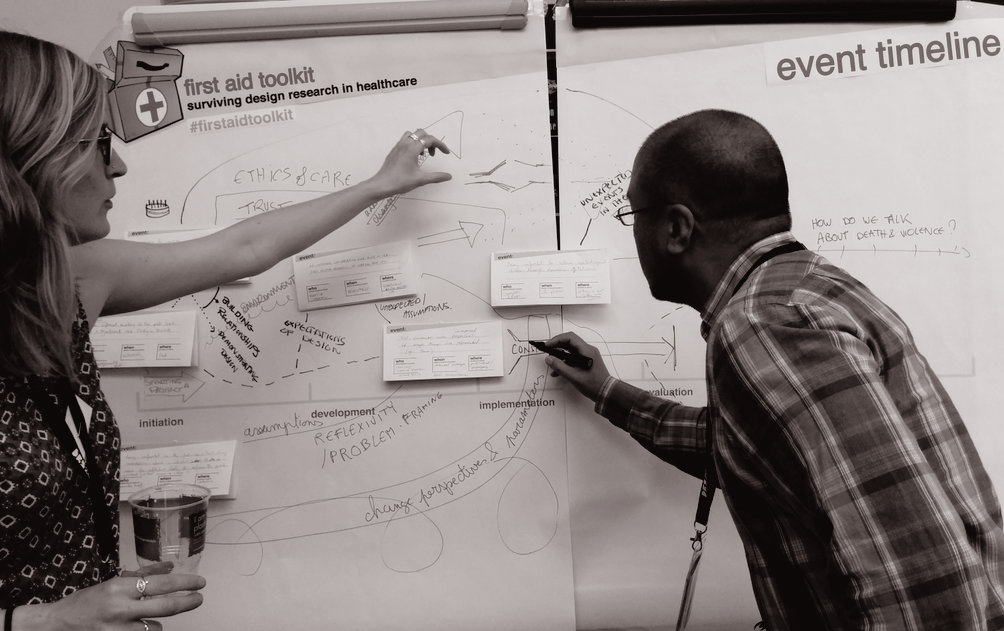

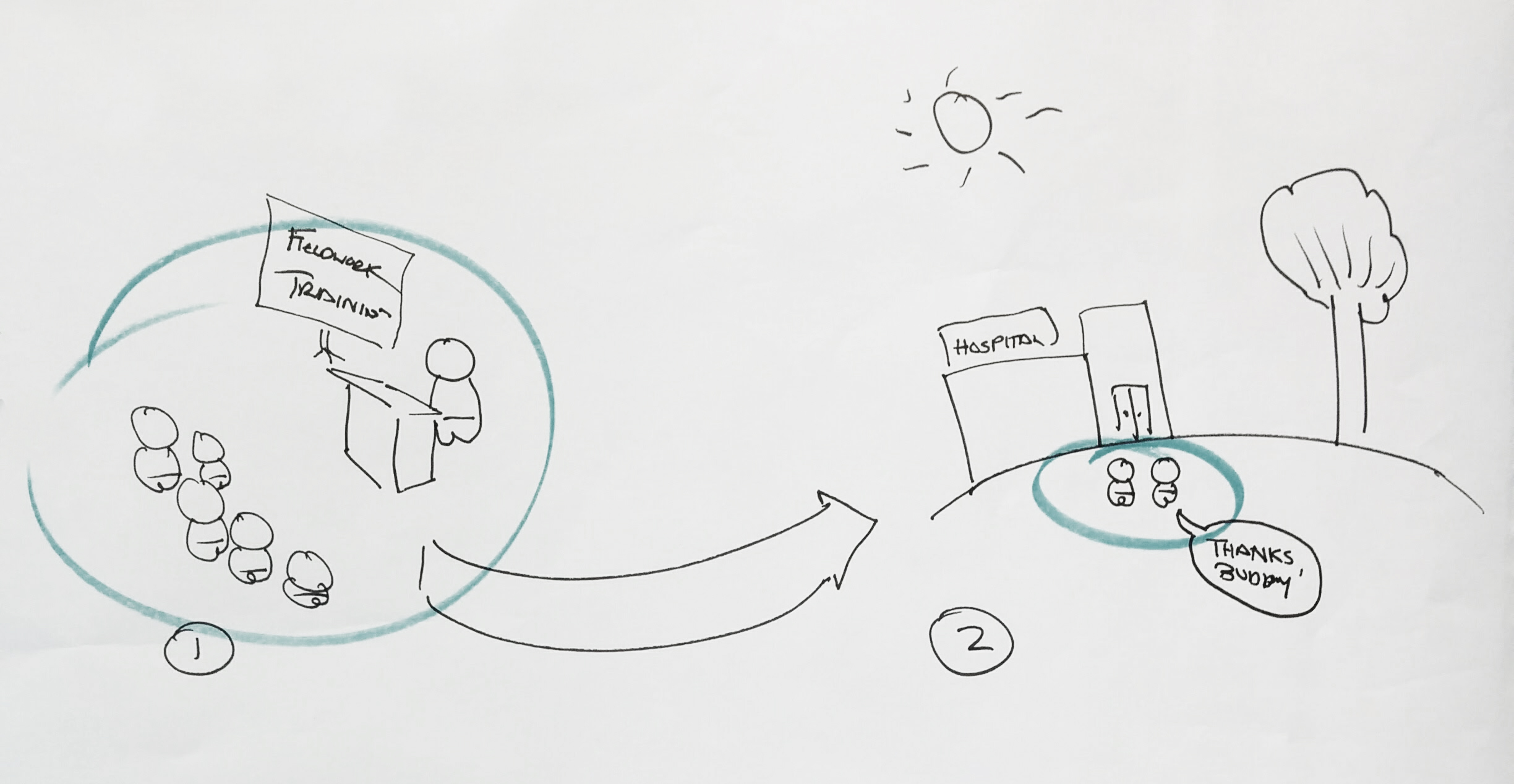

The participants working on the strategy ‘care and reflexivity’ seemed to have arrived on the topic of self-protection by elaborating on the concept ‘tools for training’ (fig. 3).

They expatiated from the idea of psychotherapy for researchers and self-care, which was described by the participants as providing accessible support when people are in crisis by recognizing moments of need. As a final solution, they suggest a check-in ‘Buddy’ as part of a system that helps to protect both researchers and participants and prepare them before the actual field work. For example: the ‘Buddy’ could shows the designer how to develop a good disengagement strategy when he gets too involved with care.

It is important for designers working in a health care to realize that they are not trained for this context, in contrast to the clinical staff they are working with. The unfamiliarity, high stakes and stress related to (health) care may be unique to this context and poses its own threats to good practice design research. Self-protection, for instance by providing a ‘buddy system’ as describe above, is a strategy that calls for further exploration.